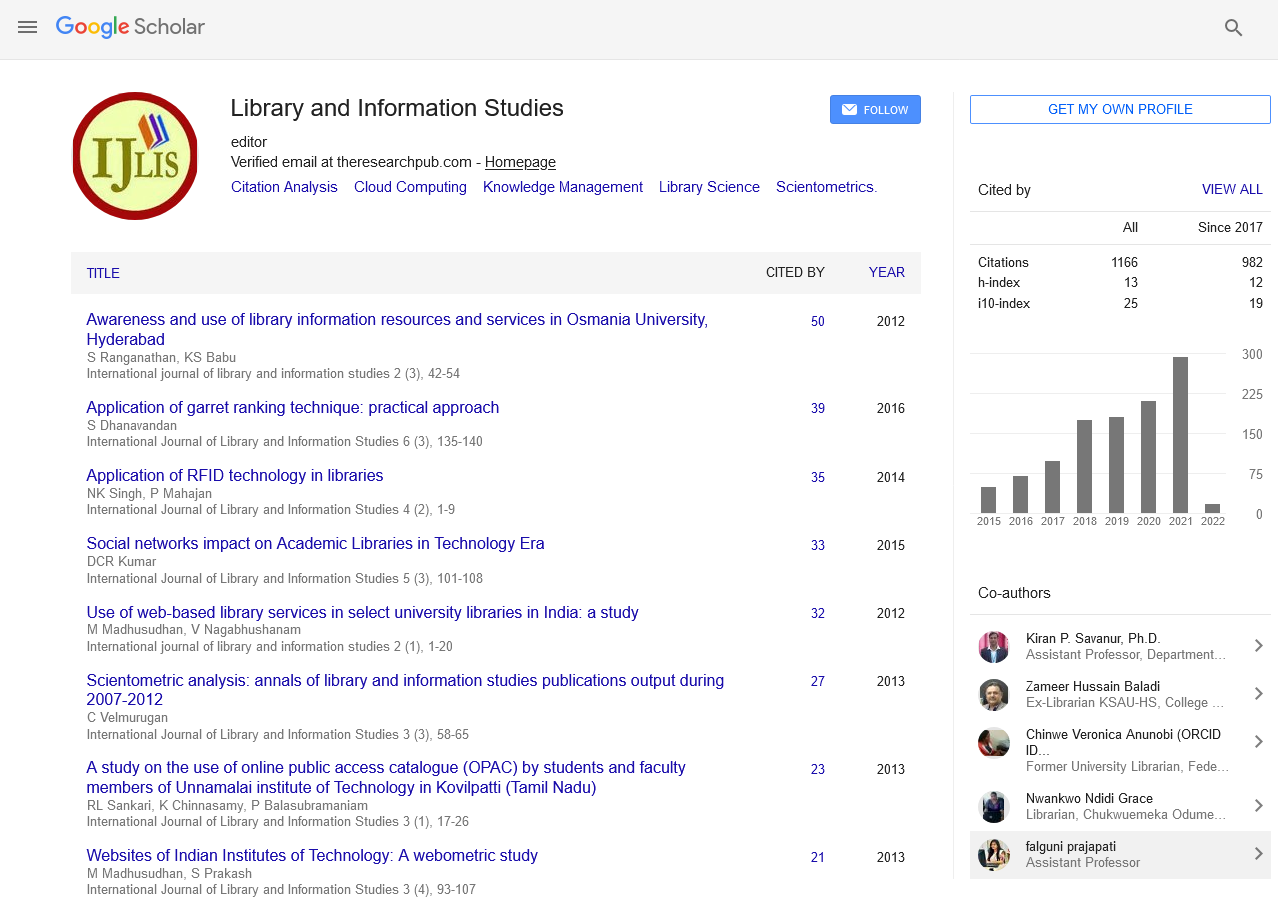

Review Article - (2022) Volume 12, Issue 3

A Multifaceted Approach: Information Literacy Instruction for Emerging Young Adults

Catherine Baldwin*Abstract

As academic librarians, we teach adolescent, adult and young adult students to access and utilize resources, many of which are accessible only through library services while students are matriculated within higher education settings. Therefore, librarians must also support the development of students’ critical thinking skills and research processes so that after graduation students will be empowered within their working and daily lives through well-developed information literacy skills. Librarians may provide highly effective instruction to support and guide students through meaningful research processes and their development of information literacy skills by understanding the cognitive development that traditional-aged college students experience while maturing from adolescence to young adulthood. By utilizing both pedagogical and andragogical instruction methods, instruction services librarians will better assist university students as they grow into independent, organized, critical thinkers who will maneuver smoothly through a complex information landscape on campus and beyond.

Keywords

Information Literacy, Andragogy, Pedagogy, Instruction Methods, Lifelong Learning.

Introduction

When designing information literacy instruction, academic librarians must consider the question “Who are my students?” The answer is complex and worth considering. Such critical thinking about students enables librarians to provide beneficial instruction for an increasingly essential form of literacy. Today's university student population is diverse across several variables: backgrounds, cultures, gender identity, race, technological savvy and access, abilities and challenges, family situations and home environments, languages spoken, affluence, age, ethnicity, and nationality. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the increase in online instruction across all levels of education have necessitated diverse learning environments of online and online/in-person hybrid courses. Instruction services librarians consider these variables when offering information literacy instruction for optimal learning outcomes.

Developmental Level and other Facets of Student Diversity

Statistics illustrate that the United States’ population is diversifying through population growth and immigration, and campuses reflect these changes (Johnson, 2020). Academic librarians and discipline-specific faculty are met with the challenge to reach students "where they are" personally, academically, technologically, culturally, and regarding information literacy. As information specialists, librarians teach students across discipline areas and age groups, while also working, assisting, and collaborating with faculty; therefore, our professional information literacy skills are continually evolving. The resulting flexibility and awareness add dimension to librarians’ teaching and research services. When addressing students, a unifying, elemental factor guiding librarians’ instruction is their age.

When considering variables affecting learning, librarians recognize that age and development is complex, driving forces with instructional implications. Essentially, adolescents are “advanced children” maturing into adulthood. Due to the physical, and therefore cognitive, development occurring during adolescence, it is necessary for instruction services librarians to acknowledge differences between adolescents and young adults in matters of physical, cognitive, and psychological development. This is especially critical as undergraduate students enter college within one state of maturation and leave within the other. However, student development and correlated teaching methods exist on many levels, with a number of mature students requiring methods associated with younger students and vice versa; flexibility within instruction is key. Therefore, teaching information literacy within a setting of higher education requires librarians to utilize techniques addressing both ends of this developmental continuum, requiring a mix of new pedagogical approaches.

Faculty librarians must blend teaching methods for the best fit for an undergraduate student population. The process may seem complicated but is less daunting when one considers that students’ cognitive development, and corresponding teaching methods, may be adjusted along a continuum. Blending and re-blending instruction to best fit the development of students will be worth the effort as students benefit from cognitive and behavioral techniques supporting their developmental levels. Providing efficient and effective information literacy instruction is especially necessary for faculty librarians who must impart a great deal of information within a limited timeframe, as during one-shot instruction sessions of less than one hour. It is noteworthy, then, that developmentally appropriate teaching methods will foster efficiency and improve impact during instruction.

It is important to recognize that replicating the same learning experience for each student group is difficult and unnecessary, even if teaching one lesson to multiple classes. Librarians may adjust the degree of independence within an activity to meet the maturity of each class, adjusting the activity as needed during the lesson. For example, a less mature student group may require didactic, prescriptive methods over another more mature and independent class possessing greater research experience. Each time librarians teach information literacy skills; their student group is comprised of a unique set of individuals, which calls for flexibility in teaching. However, there are basic guidelines for teaching maturing adolescents and young adults to encourage their curiosity through meaningful learning experiences.

For this article, the focus will rest upon popularly accepted definitions, boundaries, and implications of pedagogy and andragogy within North America, as well as the originating European perspective.

Information Literacy: Pedagogy and Andragogy

According to the United Kingdom's Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals’ (CILIP) revised definition, "information literacy is the ability to think critically and make balanced judgments about any information we find and use. It empowers us as citizens to develop informed views and to engage fully with society" (Secker, 2018). This noble definition of information literacy addresses participating in society with reliable information tools and skills to the benefit of all. This lofty perspective contrasts with the pragmatic mindset faculty librarians must often consider when designing one-shot instruction sessions for freshman composition classes, for example. However, lifelong learning goals begin through the acquisition of a string of singular skills (Grassian, 2017). Even this definition has been revised from a previous, more transcribed set of skills, expanding the definition to a broader set of empowering goals (Secker, 2018). As this is certainly not the only example of a revised definition by information literacy professionals, it does indicate a trend. The Association for College and Research Libraries (ACRL) encourages a similar approach, as “Information literacy is the set of integrated abilities encompassing the reflective discovery of information, the understanding of how information is produced and valued, and the use of information in creating new knowledge and participating ethically in communities of learning” (2016, p. 8).

Historically, the split of education into pedagogy and andragogy was delineated within a text by Alexander Kapp of Germany, in 1833, when the need arose to differentiate between the education of adults and children (Loeng, 2018). One hundred years later, the concept of adult education was readdressed by German author Rosenstock-Huessy and gained momentum, leading to Germany’s educational institutions and camps, with the focus of adult education being the improvement of society through betterment of the individual (Loeng, 2018). Unfortunately, the initial intention of bringing people together across social strata took a dark turn preceding World War II, and these systems of popular education were temporarily utilized for tangential purposes (Loeng, 2018).

Simply put, andragogy implies the education of adults, while pedagogy denotes the education of children. Pedagogy begins in infancy and extends even longer than one remains childlike. Technically, a person remains a child until their brain and body fully develop by around age 25 (Crone, 2017). This should be considered when teaching traditional college students who earn undergraduate degrees prior to reaching this developmental milestone (Crone, 2017). Within the United States, adolescent students may vote, marry, join military service, adopt legal independence, serve adult penalties within the legal system, drive, and graduate from university before they have reached physical and cognitive adulthood.

Cognitive Development and Learning Implications

As educators, it is imperative that we honor students’ developmental stages. The study of this confluence of cognitive development and educational theory has resulted in a newly developed discipline, known as "educational neuroscience" (Crone, 2017). Adolescent students may appear to be slacking and unorganized, but they are experiencing very real physical, cognitive, and hormonal changes, which affect their studies, learning, moods, and behaviors. Their increased need for sleep is an example. While requiring nearly ten hours per night, students’ natural ability to fall asleep shifts toward late evening (Crone, 2017). This causes difficulty as the adult world values waking early; however, early morning instruction for first year students may be especially challenging. Sleep deprivation may also negatively affect adolescent students' immunity, mood regulation, brain development, and ability to learn, impacting their ability to succeed in their studies (Crone, 2017).

Cognitive maturity occurs when two areas of the brain, the frontal cortex and the amygdala, have developed fully (Crone, 2017). Consisting of the front portion of the brain, the frontal cortex is large and complex, controlling several executive functions (Crone, 2017). Executive functions are processes which include planning and self-control behaviors; behaviors most associated with maturity (Crone, 2017). The frontal cortex is also responsible for decision making and enables a person to predict long-term consequences. Unfortunately, the frontal cortex is also the area of the brain most often damaged due to its prominent location, and injury to this area can affect drastic consequences to planning and self-control abilities, affecting working memory and limiting selfsuppression of socially inappropriate behaviors (Crone, 2017). A student's frontal cortex development may be expressed by the risks they take, their inconsistency and quality of mood, and their degree of organization. The amygdala is also in rapid development during the late teen years. Located deep within the brain, it regulates mood stability (Crone, 2017). As noted, brain development is incomplete for older teens who attend university following high school. From a librarian's perspective, it makes sense that Young Adult literature is rife with drama, as it reflects the experiences and intense emotions of teens and cognitively developing young adults.

Traditional-aged first year college students are emerging from childhood and developing into young adult learners. As they continue their formal education, traditional college students between 18 and 22 years of age tend to be more extrinsically motivated than their elder classmates (Conaway & Zorn-Arnold, 2008). Therefore, these students benefit from structured due dates and clearly specified assignments with implications of rewards and consequences. Accustomed to a lighter workload during high school, freshman students may express impatience with lengthy readings and involved assignments, and they may resist spending time researching within scholarly databases, preferring Google for quick bites of information, regardless of its suitability to their purposes.

A lack of organization also affects less mature students, as demonstrated through lost work, forgotten assignments, missed instruction, and last-minute research. With a limited perspective, younger university students may feel overwhelmed by college requirements and perform unsatisfactorily during guided research instruction. This is especially true as young students are likely to overestimate what they may accomplish within an hour's time, due to lack of research experience within a university setting. Less mature college students are also required to complete general education courses and life skill seminars, which tend to be teacher-centered and serve to provide students with a broad base of general knowledge as well as the skills needed to complete their university education. With their lack of foresight, many young college students fail to understand the long-term benefits of such experiences, including information literacy sessions, and fail to give them adequate attention.

For librarians, student maturity is often demonstrated by senior students, who pine poetic regarding the benefits of consulting with librarians while completing research for their final and culminating capstone course. As more experienced and mature students, graduating seniors appreciate information literacy lessons and resources they reluctantly received as freshmen. Seniors often draw together the information literacy instruction they experienced throughout their time at university. Thankfully, students’ perspectives, skill sets, and cognitive development finally converge within this eureka moment.

Pedagogical Teaching Elements

Goals and educational decisions for young children are mainly chosen by educators to guide students down an educational path, with less choice left to younger students. This approach accommodates less mature students' lack of perspective, foresight, and organization (Conaway & Zorn-Arnold, 2008). While occasionally prescriptive, teacher-guided learning does not imply lack of creativity and input by students when gauged according to executive function development. Rather, appropriate teacher guidance enables students to engage fully. To describe pedagogical teaching methods for information literacy, the developmental maturity of students must be considered. Young children begin their information literacy journey as new canvases, with educators preparing them with layers of general knowledge through subject-focused, teacher-supported strategies. First year college students are obviously more advanced in their knowledge base than young children, yet they fall at the end of this developmental spectrum, and therefore benefit from relevant teaching and learning strategies, such as direct instruction. New information and comprehension adhere more strongly to minds prepared with a base of generalized knowledge (Conaway & Zorn-Arnold, 2008). Therefore, applied research experiences and supportive instruction enable traditional-aged college students to effectively add color to their information literacy canvas.

Pedagogy, or the instruction of children and teens, involves teaching general information to enable students to build a knowledge base. As they grow and mature, students supplement this base knowledge with greater detail; their learning grows as they mature. Pedagogy is also structured, with the educator designing lessons and coordinating curricula, assigning work with explicit and clear directives, and avoiding ambiguity. These external strategies guide students to organize their thinking and study skills, which they will continue to apply as adults. Pedagogical curricula are also often organized, taught, and learned by subject rather than through a more cohesive, integrated approach. However, progressive educators recognize the benefits of teaching across curricular areas when possible, keeping an eye on students’ mastering foundational skills and material. Generally speaking, pedagogy is teacher-centric, as the educator leads classroom organization, subjects taught, and most classroom activity.

A more student-centric approach has emerged in recent decades to allow for greater choice and student input within assignments. This is especially appropriate as young college students are mature enough to fully participate in their learning decisions and are capable of metacognition. However, it remains that young university students, who fall within the developmental bracket of ‘children’ often lack background experience and perspective due to their age and inherently limited experience. Therefore, information literacy pedagogy still requires detailed explanation and somewhat didactic instruction to fill the gaps in student experience.

According to Conaway and Zorn-Arnold (2008), one’s experience exists within two realms: the psychological and the physical. Teachers of young students provide concrete, hands on activities that provide physical experiences to enable students’ creation of understanding, and teachers share their own background experiences through storytelling and explanation to create shared psychological experiences with their students (Conaway & Zorn-Arnold, 2008). Although university students are more mature than young children, pedagogical instruction through scaffold, supported, learning frameworks remains beneficial to college students between the ages of 18-22 years.

Pedagogical Information Literacy Instruction for Traditional Aged College Students

Pedagogy includes methods which provide structure and guidance to maturing students; instruction services librarians provide clear structure during lessons and assignments to encourage student autonomy without granting too much flexibility, which may cause confusion. Because pedagogy dictates that educators hold the greater degree of responsibility within the teacher-student relationship, instruction services librarians may provide research assignments and experiences to foster independence according to student maturity.

During information literacy instruction, librarians can support students through clear expectations and connections to resources, while also encouraging personal choice of topics, databases, and pathways for research. Choosing research topics of personal interest fosters students’ natural curiosity and may provide them with opportunities to further explore their major areas of study. Librarians can also enhance students’ personal comfort with research processes by allowing students to use personal cell phones and laptops in class. This instructor flexibility opens communication with and meets students closer to “where they are.” This approach also encourages students to develop positive associations with research and information literacy skills while employing technology with which they are familiar. It is worth noting that these strategies are also in keeping with Universal Design for Learning (UDL) techniques, opening more doors to more students.

While librarians may assume that digital natives are technologically savvy, The Dunning-Kruger Effect is often demonstrated by young college students through inflated assumptions of personal information literacy and technological skills (Keiser, 2016). This is understandable since today’s adolescents have integrated technology into most aspects of their daily lives and feel more comfortable with it than without it. However, first and second year students still require guidance in technology-related information literacy skills, including choosing reliable sources, assessing social media and news media through critical thinking, understanding provenance and intent behind publicized information, and accessing and searching databases and OPACs (Online Public Access Catalogs).

In addition to providing scaffold, personalized learning experiences and technological guidance, instruction services librarians best assist adolescents by acknowledging the challenges they experience regarding a basic cognitive function; maintaining attention. Adolescent students are less focused than more cognitively mature counterparts. Maintaining attention during instruction may be more difficult for less mature groups, especially if a lesson includes several detailed steps and processes, or if a librarian teaches a great volume of information within one session. This is especially challenging, as librarians restricted to fifty-minute instruction sessions attempt to include as much information as possible. Distractions by classmates during group work, text messages received during class and overall fatigue also challenge student focus (Crone, 2017). This is something to consider when teaching research activities, particularly with one-shot instruction sessions. Instruction services librarians may support student learning in several simple ways: offering written outlines for note taking, sharing examples of proper citation, and listing suggested research pathways on presentation slides and handouts. These simple additions will support student focus on research processes, enable students to work more independently, and improve efficiency during instruction.

Andragogy: A Brief History

Traditional college students begin higher education as adolescents but graduate on the cusp of adulthood. However, physical, psychological, and cognitive maturity vary for each person, so faculty librarians must provide exercises and instruction which reflect the experiences and autonomy of maturing learners. In borrowing a cliché approach to defining a concept, it is worth noting that the Concise Oxford English Dictionary excludes the term "andragogy," yet the related term "adult education" is listed, with references to "continuing education, e-learning, and community college" (Soanes & Stevenson, 2008). This demonstrates the ambiguity of terms referring to teaching adult students, as well as the variety of philosophies implied. When breaking the term into its phenomenological parts, we see that "Andre" translates to "man," who is problematic in terms of gender implication; a more inclusive term is "treilagogy," addressing all people (Loeng, 2018).

While it may seem surprising today, andragogy, referring to the education of adults, was historically the original focus of education; pedagogy is a relatively new concept. Dating to Plato in Ancient Greece, adult education was synonymous with education; for a very long time, there was no allusion to levels of education delineated by age groups (Felts an, 2017; Loeng, 2018). While there is dispute over the fine points of adult education, or “AE," versus "andragogy," the term “andragogy” is now commonly adopted as referring to the education of adults.

Over time, apprenticeship developed as a form of AE, as did correspondence schools for useful skills such as shorthand (Felts an, 2017). By the 1830s, Alexander Kapp published a book in Germany which set into motion a more formal consideration of the concept of andragogy, with its focus being social reform through betterment of the individual, as well as the breaking of social barriers preventing progress (Loeng, 2018). Tragically, this movement was later abused for political purposes within the Work Camp Movement. Fortunately, after WWII, the original intent of adult education was restored, and the concept spread to nations surrounding Germany. The authors Rosenstock-Huessy, Lindeman, Buber, and Picht were among the most influential proponents of adult education as the movement gained momentum throughout Europe (Loeng, 2018). During this era, Hanselmann published a text portraying andragogy as "self-education," shifting the locus of control to the adult student, and Poeggler was credited with lending scientific credence to the field of study (Loeng, 2018).

Following WWII, the need for social diplomacy through an educated populace freed access to education from its ivory tower of wealth and privilege, becoming available to common people (Felts an, 2017). During the 1950s, then-Yugoslavia's University of Belgrade offered adult education as an area of study under prominent faculty Dusan Savicevic, while Knowles also focused on the concept in the United States (Sopher, 2003). Savicevic attended a seminar offered by American Knowles at Boston University in 1966, during which Savicevic labeled Knowles’ topic as andragogy; a concept which Knowles had conceptualized under the term ‘adult education’ (Loeng, 2018; Sopher, 2003). A few years later, Knowles authored the text "The Modern Practice of Adult Education: Andragogy versus Pedagogy," thereby raising to prominence the oft-debated term “andragogy," reaching unprecedented numbers of readers, and firmly establishing the field of adult education as an accepted discipline of academic study in North America (Loeng, 2018).

Adult Education (AE) continues to gain attention within the United States as an essential form of education, despite a historical emphasis on K-12 (Kindergarten through grade twelve) followed by potential enrollment in a university. However, as social equity and access to information become ubiquitous with social justice and equal opportunity, adult education outside of formal education shines continually brighter for the benefit of society, as well as the individual (Feltsan, 2017). As Knowles stated in 1980, adults living within the 20th century experienced four times the number of social changes in their lives as those living during previous centuries (Feltsan, 2017). With technology increasing the speed of living and communicating within the 21st century, one could argue that there exists potential for an even greater number of shifts in social change during this century. Therefore, the need for adult education programs exists and is expanding. Social movements, protests, public health updates, and political developments are broadly discussed through journalism and social media, increasing the potential for viral spread of misinformation and disinformation. Therefore, one could make a strong argument for increased need of generously funded public education for adult learners within a rapidly evolving society.

Variations of AE appear to be tethered geographically to events and cultures, with each region claiming a relative within the expansive family of andragogy’s development (Loeng, 2018). However, the most widely known perspective is that of American Malcolm Knowles, whose text has become ubiquitous with andragogical study. In the least, therefore, it is imperative that faculty librarians, who teach emerging adults, become familiar with what Knowles expostulated through his work.

As previously stated, Knowles remains the most well-known advocate for adult education, especially within North America. Knowles considered adult learners as increasingly independent and self-directed as they mature, benefitting from personal background experiences, relating learning to their community status and roles, and possessing a readiness to apply newly learned knowledge immediately and in practical ways (Loeng, 2018). Knowles also proposed that students, who regard themselves as adults and adopt the roles of adulthood, may also qualify for adult education experiences and teaching methods, despite their youth (Feltsan, 2017). These adjustments align perfectly with young adult learners who are maturing and gaining independence throughout their college years.

There are disagreements among educators, however, regarding the various shades of meaning within the discipline of andragogy. Some believe that Knowles lacked scientific evidence supporting his claims; others disregard his consideration of adult education as being separate from children's education, rather than treating education as a continuum; and other researchers feel that Knowles ignored the interconnectedness of learning, adulthood, and societal influences (Loeng, 2018). However, many involved in the research and practice of andragogy appreciate the spotlight shone upon the field, as well as the resulting progression of interest in its empirical study. Current efforts include the German University of Bamberg’s establishment of a faculty chair for promoting and researching the scientific aspects of adult education, with an emphasis on "life wide" learning, encompassing both formal and informal learning experiences (Loeng, 2018).

Characteristics of Adult Learners

While most adolescents attend institutes of higher education as an extension of their K-12 education, nontraditional students often return to campus to complete degrees which were disrupted. When teaching classes including both traditional and nontraditional students, the differences in development between the two groups often become evident to instruction services librarians. Adult learners tend to be self-motivated with a specific end goal in mind (Conaway & Zorn-Arnold, 2008). They enter university because they have identified a gap within their education, and they wish to fill this gap to attain a practical goal; a degree and resulting occupation, both with immediate and long-term impacts. Adult learners tend to be more patient and willing to put in the time and effort necessary to accomplish goals, taking the necessary steps to do so successfully (Conaway & Zorn-Arnold, 2008). Organization of time, money, appointments, resources, personal lives, and learning materials comes more easily to mature students, as well. Adult students possess perspective on struggles they experience during learning and recognize difficulties as temporary and worth enduring (Conaway & Zorn-Arnold, 2008). However, adult students’ maturity also creates resistance to some learning situations, including assignments and lessons lacking apparent relevance to their personal goals. It is important that librarians realize that adult students desire educational experiences that directly support their major area of study, and they expect to apply this information as soon as possible through a problem-solving educational experience.

Awareness of adult students’ personal lives is also important. Adult learners and maturing adolescent learners often operate under restraints including childcare, work schedules and demands, and challenges to finances, time, food, and energy. Each of these elements test mature students' commitment and resolve to complete their program of study, and instructor flexibility allows mature students to choose how and when to complete assignments. Supporting this concept is Knowles' philosophy that the focus of adult education must include the student as an active participant (Knowles et al., 2011; 2005). Knowles honored the active role adult learners should take within assignments and research sessions by acknowledging their desire to develop skills to a high degree, expand their learning, and deepen self-awareness (2011; 2005). Incorporating choices and personalization will address adult learners’ psychological need for respect and autonomy, as will provide resources and guidance within a framework for learning and applying new information (Feltsan, 2017).

According to Knowles, educating adults involves six elements: the role of experience, self- directedness, curiosity and the need to know, readiness to learn, personal orientation toward learning, and internal or intrinsic motivation (Conaway & Zorn-Arnold, 2008; Knowles et al., 2011; 2005). Many of these elements contrast with the educational readiness of younger learners, who have yet to benefit from broad personal experience and the resulting network of background information into which they may weave new information. The discipline required for selfdirected learning involves many skills developed throughout adolescence and young adulthood, as well as organizational skills to manage learning resources, and the motivation to do so for delayed benefits. Therefore, as adolescent university students begin their degree work, the skills necessary for academic success are still under development. However, more mature, nontraditional, and upper-class students (juniors, seniors, graduate students) possess strong advantages, as they are more cognitively mature and can rely upon a larger bank of personal experience to better manage challenges within the freedom and demands of a university setting.

Information Literacy Instruction for Emerging Adult Learners

Due to the developing self-awareness and metacognitive capabilities of emerging young adults, “self-assessments” of information literacy skills are valuable tools for traditional age college students. Self-assessments enable students to critically assess their personal development, especially if these skills are structured within coursework. When taught at the beginning of assignments and reviewed after completion, information literacy self-evaluations encourage student ownership of learning, goal-building for immediate application, and awareness of one's skill development (Keiser, 2016). Instructors, who offer self-assessments at the start of class, assignments, or even at the beginning of a semester, may adjust instruction to fit class-or student-specific needs, as well (Keiser, 2016). Incorporating explicit information literacy instruction within courses will clarify what information literacy are, the skills involved, and the connection between those elements and librarians and services. The great value of such clarification and the meaningful application of information literacy skills make offering this kind of collaboration between faculty and librarians extremely beneficial to students, especially when offered at the beginning of their formal education. Faculty-librarian collaborations for course content and implementation of information literacy skills will benefit students, relieve academic burden, and clarify librarians' roles within students’ education and academia in general.

Increasing numbers of students now participate in online courses, especially since the COVID- 19 pandemic began. Online information literacy instruction creates new challenges and opportunities for librarians to teach students and to collaborate with other faculty. According to Halpern & Tucker (2015), nearly half of all college students within the United States have taken an online course, prior to the pandemic. Most students, regardless of age and education level, have taken courses online during the pandemic. This creates a new cultural and educational option which will persist in the future. However, online learning has been the norm for years within community colleges and educational programs catering to adult learners. Community colleges and their librarians have sat at the forefront of online learning due to the convenience of such programs to their adult student population.

Regardless of the type of educational institution, librarians have many options for providing online information literacy instruction. Collaborating with faculty enables librarians to join courses as co-instructors in online learning management systems like Canvas. Holding virtual office hours, offering online orientation sessions, and posting recorded tutorials and flipped learning objects are methods for connecting with students within the virtual environment (Halpern & Tucker, 2015). Joining classes synchronously for instruction is another option, through platforms like Zoom and Microsoft Teams. Because community college librarians are especially adept at these skills, librarians new to online work benefit from their colleagues’ expertise, as they are accustomed to working within both digital and traditional classroom environments to best serve adult students’ needs (Halpern & Tucker, 2015). Tutorials, for example, may be posted within libguides or within course sites for convenient access and students may view digital learning objects according to their personal schedule. This enables a flipped experience, saves scheduled class instruction time, and allows for deeper in-class learning (Halpern & Tucker, 2015).

A basic, and perhaps unexpected, way for librarians to support student learning is through purchasing print resources and making them available in addition to eBooks. According to ARFIS (Academic Reading Format International Study) research group, more than 78% of college students interviewed worldwide prefer to learn from print materials, rather than from digital materials (Mizrachi et al., 2018). This is especially true for readings longer than seven pages and for learning complex material (Mizrachi et al., 2018). Students worldwide reported better focus and retention of material read and interacted with on the printed page (Mizrachi et al., 2018). With this in mind, librarians must advocate for low cost or free printing services if also advocating for the adoption of digital materials, such as open access materials. This is especially important, considering the global push toward digital materials across all levels of education in reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, librarians must remember that physically interacting with print materials through annotating, highlighting, and note taking assists learning. Therefore, librarians may consider teaching the utilization of digital tools for interacting with eBooks and online articles, especially if print materials are not available or viable.

Collaboration with Faculty

With information literacy rapidly integrating with students' daily educational experiences, librarians will also benefit from understanding faculty perspectives on information literacy. Generally, faculty view information literacy as important; accessing and retrieving information are essential skills for students, and faculty regard critical thinking about information and information sources as necessary (Bury, 2016). In commiseration with librarians, faculty are also frustrated by students’ reliance upon the search engine Google for information, rushing to locate resources, and considering only initial sources discovered (Bury, 2016). In alignment with novice information literacy skills, students tend to accept information they see at face value rather than critically questioning the quality and provenance of information and its source (Bury, 2016). However, within a two-year study from 2010-2012 on faculty perspectives on information literacy, many faculty defined information literacy as including the seeking and accessing of information; yet respondents excluded why and how to apply information once found (Bury, 2016). This demonstrates the importance of librarians’ guiding students toward deep, meaningful application of information gained through critical research processes. Otherwise, the point of seeking and accessing information lacks purpose. For example, exploring and narrowing topics employ high level information literacy skills which require creative thinking; skills supported by faculty librarians.

While there are several reasons for librarians to collaborate with faculty, one of the most essential may be to create instructional balance. Students often request research help from course faculty rather than librarians, when information literacy skills are integrated into coursework and assignments (Bury, 2016). With the increase in digital learning environments and resources, this tendency may become exaggerated. Students may contact only their professors for clarification and guidance regarding information literacy skills, especially as information literacy becomes more deeply integrated into most learning situations. Therefore, librarians must clarify with students and faculty their expertise regarding information literacy, encouraging direct access to and familiarity with librarians for student consultation and faculty collaboration.

Within our increasingly digital lives, the line between information and traditional literacies is blurring (Bury, 2016). As literacies merge and overlap, librarians must collaborate with faculty across discipline areas to incorporate information literacy skills into curricular areas and to monitor their implementation. According to Bury (2016), faculty within higher education cite the need for student awareness of research resources beyond Google and Wikipedia, and with the ubiquitous nature of digital documents within higher education, print resources have become novel to university students. Librarians must provide students with physical experiences of handling a variety of resources, enabling students to differentiate between types of scholarly communication: journals, articles, magazines, trade magazines, books, peer reviewed journals, etc. Due to the ethereal nature of information born digitally, university students struggle to differentiate between resource types and their best uses. With increased access to digital resources in reaction to COVID 19, as well as increasing adoption of Open Education Resources (OER), it is tempting for students to align all digital resources on the same plane for quality, quantity, value, and purpose. However, librarians must provide guidance and clarification regarding these resources to a degree which was unnecessary within a more physical information ecosystem of print materials. Interestingly, young adult students appreciate manipulating and creating physical items, as evidenced by the popularity of vinyl records, nib ink pens, sewing embroidery, and DIY projects. As in most endeavors, one's mindset is also key to an approach to learning, as assumptions guide one’s actions. As an example, students commonly assume that they are searching for a single, correct answer during research. Within this mindset, students regard information and scholarship as a singular and hidden solution waiting to be discovered, rather than an academic conversation consisting of many facets, paths, and outcomes. When students realize that research is a creative process, scholarship becomes a personal endeavor, rather than an arduous test of endurance and perseverance. Also, because scholarship involves communication, librarians must also teach young adult students that research involves seeking and valuing multiple viewpoints, rather than using research only to justify one's personal perspective. This is especially important for personal buy-in by older teens and young adults who perform their best work when dealing with issues that are personally valuable and display credibility (Conaway & Zorn-Arnold, 2008).

Conclusion

As academic librarians, we teach adolescent, adult, and young adult students to access and utilize resources, many of which are accessible only through library services while students are matriculated within higher education settings. Therefore, librarians must also support the development of students’ critical thinking skills and research processes so that after graduation students will be empowered within their working and daily lives through well-developed information literacy skills. Librarians may provide highly effective instruction to support and guide students through meaningful research processes and their development of information literacy skills by understanding the cognitive development that traditional-aged college students experience while maturing from adolescence to young adulthood. By utilizing both pedagogical and andragogical instruction methods, instruction services librarians will better assist university students as they grow into independent, organized, critical thinkers who will maneuver smoothly through a complex information landscape on campus and beyond.

References

- Association of College and Research Libraries. (2016, January 11). Framework for information literacy for higher education: Introduction.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Bury, S. (2016). Learning from faculty voices on information literacy. Reference Services Review, 44(3), 237-252.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Conaway, W. & Zorn-Arnold, B. (2008). The keys to online learning for adults: The six principles of andragogy. Distance Learning, 12(4), 37-42.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Crone, E., & ProQuest (Firm). (2017). the adolescent brain: Changes in learning, decision-making and social relations. Routledge.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Felts an, I. (2017). Development of adult education in Europe and in the context of Knowles′ study. Comparative Professional Pedagogy, 7(2), 69-75.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Grassing, E. (2017). Teaching and learning alternatives: A global overview. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 56(4), 232-239.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Halpern, R. & Tucker, C. (2015). Leveraging adult learning theory with online tutorials. Reference Services Review, 43(1), 112-124.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Johnson, S. (2020). A changing nation: Population projections under alternative immigration scenarios. Population Estimates and Projections: Current Population Reports. United States Census Bureau.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Keiser, B. (2016). How information literate is you? A self-assessment by students enrolled in a competitive intelligence elective. Journal of Business & Finance Librarianship, 21(3-4), 210-228.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Knowles, M. S., Holton, I. E. F., & Swanson, R. A. (2011; 2005). The adult learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development (7th Ed.). Elsevier.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Loeng, S. (2018). Various ways of understanding the concept of andragogy. Cogent Education, 5(1), 1-15.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Mizrachi, D., Salaz, A., Kurbanoglu, S., & Boustany, J., on behalf of the ARFIS Research Group. (2018). Academic reading format preferences and behaviors among university students worldwide: A comparative survey analysis. Plos ONE 13(5): e0197444.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Secker, J. 2018. The revised CILIP definition of information literacy. Journal of Information Literacy, 12(1), pp. 156-158.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Soanes, C., & Stevenson, A. (2008). Concise Oxford English Dictionary ([Updated] 11th, rev. Ed.). Oxford University Press.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Sopher, M. J. (2003). An historical biography of Malcolm S. Knowles: The re-making of an adult educator. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

Author Info

Catherine Baldwin*Received: 22-Feb-2022, Manuscript No. IJLIS-22-55230; Editor assigned: 28-Feb-2022, Pre QC No. IJLIS-22-55230(PQ); Reviewed: 21-Mar-2022, QC No. IJLIS-22-55230; Revised: 04-Apr-2022, Manuscript No. IJLIS-22-55230(R); Published: 18-Apr-2022, DOI: 10.35248/2231-4911.22.12.836

Copyright: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Call for Papers

Authors can contribute papers on

What is Your ORCID

Register for the persistent digital identifier that distinguishes you from every other researcher.

Social Bookmarking

Know Your Citation Style

American Psychological Association (APA)

Modern Language Association (MLA)

American Anthropological Association (AAA)

Society for American Archaeology

American Antiquity Citation Style

American Medical Association (AMA)

American Political Science Association(APSA)